OpenCL Programming Guide¶

OpenCL Architecture and AMD Accelerated Parallel Processing Technology¶

Terminology¶

compute kernel :

To define a compute kernel, it is first necessary to define a kernel. A kernel is a small unit of execution that performs a clearly defined function and that can be executed in parallel. Such a kernel can be executed on each element of an input stream (called an NDRange), or simply at each point in an arbitrary index space. A kernel is analogous and, on some devices identical, to what graphics programmers call a shader program. This kernel is not to be confused with an OS kernel, which controls hardware. The most basic form of an NDRange is simply mapped over input data and produces one output item for each input tuple. Subsequent extensions of the basic model provide random-access functionality, variable output counts, and reduction/accumulation operations. Kernels are specified using the kernel keyword.

A compute kernel is a specific type of kernel that is not part of the traditional graphics pipeline. The compute kernel type can be used for graphics, but its strength lies in using it for non-graphics fields such as physics, AI, modeling, HPC, and various other computationally intensive applications.

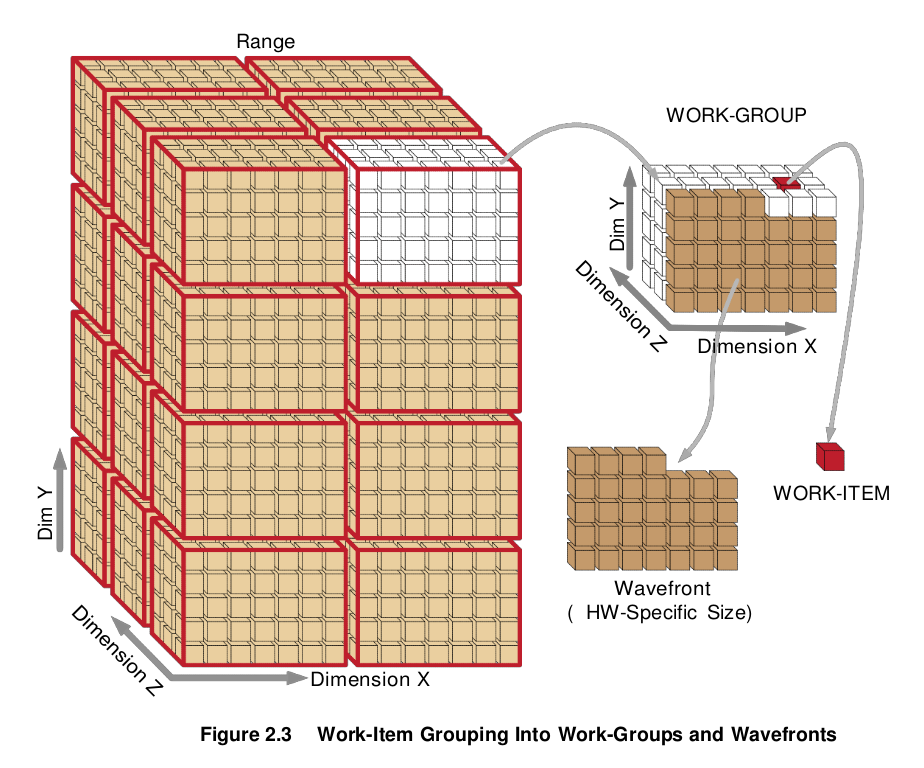

In a compute kernel, the work-item spawn order is sequential. This means that on a chip with N work-items per wavefront, the first N work- items go to wavefront 1, the second N work-items go to wavefront 2, etc. Thus, the work-item IDs for wavefront K are in the range (K•N) to ((K+1)•N)-1.

wavefronts and work-groups :

Wavefronts and work-groups are two concepts relating to compute kernels that provide data-parallel granularity. On most AMD GPUs, a wavefront has 64 work-items. A wavefront is the lowest level that flow control can affect. This means that if two work-items inside of a wavefront go divergent paths of flow control, all work-items in the wavefront go to both paths of flow control.

Grouping is a higher-level granularity of data parallelism that is enforced in software, not hardware. Synchronization points in a kernel guarantee that all work-items in a work-group reach that point (barrier) in the code before the next statement is executed.

Work-groups are composed of wavefronts. Best performance is attained when the group size is an integer multiple of the wavefront size.

local data store(LDS) :

The LDS is a high-speed, low-latency memory private to each compute unit. It is a full gather/scatter model: a work-group can write anywhere in its allocated space. This model is unchanged for the AMD Radeon™ HD 7XXX series. The constraints of the current LDS model are:

The LDS size is allocated per work-group. Each work-group specifies how much of the LDS it requires. The hardware scheduler uses this information to determine which work groups can share a compute unit.

Data can only be shared within work-items in a work-group.

Memory accesses outside of the work-group result in undefined behavior.

OpenCL Overview¶

The OpenCL programming model consists of producing complicated task graphs from data-parallel execution nodes.

In a given data-parallel execution, commonly known as a kernel launch, a computation is defined in terms of a sequence of instructions that executes at each point in an N-dimensional index space. It is a common, though by not required, formulation of an algorithm that each computation index maps to an element in an input data set.

The OpenCL data-parallel programming model is hierarchical. The hierarchical subdivision can be specified in two ways:

Explicitly - the developer defines the total number of work-items to execute in parallel, as well as the division of work-items into specific work-groups.

Implicitly - the developer specifies the total number of work-items to execute in parallel, and OpenCL manages the division into work-groups.

OpenCL’s API also supports the concept of a task dispatch. This is equivalent to executing a kernel on a compute device with a work-group and NDRange containing a single work-item. Parallelism is expressed using vector data types implemented by the device, enqueuing multiple tasks, and/or enqueuing native kernels developed using a programming model orthogonal to OpenCL.

Programming Model¶

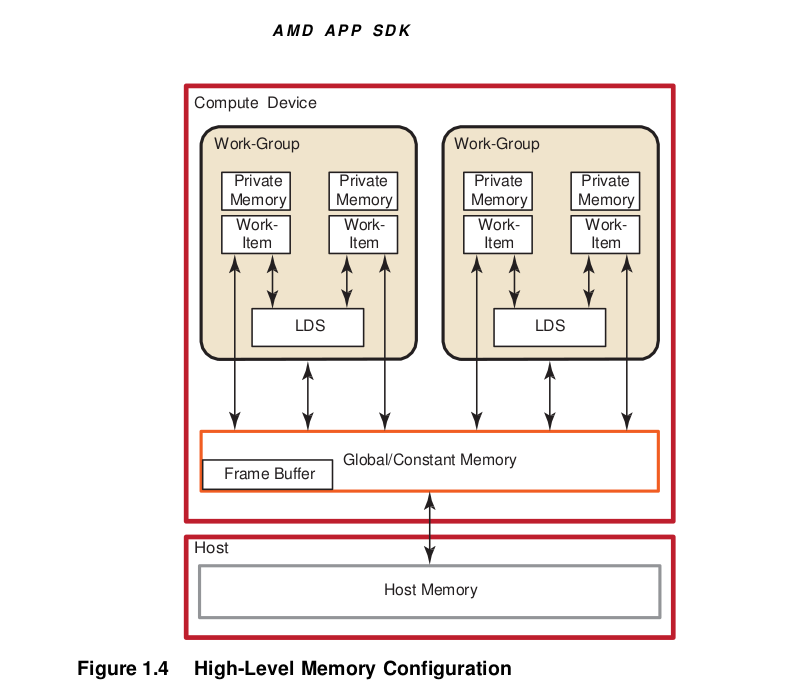

The OpenCL programming model is based on the notion of a host device, supported by an application API, and a number of devices connected through a bus. These are programmed using OpenCL C. The host API is divided into platform and runtime layers. OpenCL C is a C-like language with extensions for parallel programming such as memory fence operations and barriers. Figure illustrates this model with queues of commands, reading/writing data, and executing kernels for specific devices.

The devices are capable of running data- and task-parallel work. A kernel can be executed as a function of multi-dimensional domains of indices. Each element is called a work-item; the total number of indices is defined as the global work-size. The global work-size can be divided into sub-domains, called work-groups, and individual work-items within a group can communicate through global or locally shared memory. Work-items are synchronized through barrier or fence operations. Figure 1.1 is a representation of the host/device architecture with a single platform, consisting of a GPU and a CPU.

An OpenCL application is built by first querying the runtime to determine which platforms are present. There can be any number of different OpenCL implementations installed on a single system. The desired OpenCL platform can be selected by matching the platform vendor string to the desired vendor name, such as “Advanced Micro Devices, Inc.” The next step is to create a context. As shown in Figure 1.1, an OpenCL context has associated with it a number of compute devices (for example, CPU or GPU devices),. Within a context, OpenCL guarantees a relaxed consistency between these devices. This means that memory objects, such as buffers or images, are allocated per context; but changes made by one device are only guaranteed to be visible by another device at well-defined synchronization points. For this, OpenCL provides events, with the ability to synchronize on a given event to enforce the correct order of execution.

Many operations are performed with respect to a given context; there also are many operations that are specific to a device. For example, program compilation and kernel execution are done on a per-device basis. Performing work with a device, such as executing kernels or moving data to and from the device’s local memory, is done using a corresponding command queue. A command queue is associated with a single device and a given context; all work for a specific device is done through this interface. Note that while a single command queue can be associated with only a single device, there is no limit to the number of command queues that can point to the same device. For example, it is possible to have one command queue for executing kernels and a command queue for managing data transfers between the host and the device.

Most OpenCL programs follow the same pattern. Given a specific platform, select a device or devices to create a context, allocate memory, create device-specific command queues, and perform data transfers and computations. Generally, the platform is the gateway to accessing specific devices, given these devices and a corresponding context, the application is independent of the platform. Given a context, the application can:

Create one or more command queues.

Create programs to run on one or more associated devices.

Create kernels within those programs.

Allocate memory buffers or images, either on the host or on the device(s). (Memory can be copied between the host and device.)

Write data to the device.

Submit the kernel (with appropriate arguments) to the command queue for execution.

Read data back to the host from the device.

The relationship between context(s), device(s), buffer(s), program(s), kernel(s), and command queue(s) is best seen by looking at sample code. For an example, see the HelloWorld sample in the AMD Compute SDK.

Synchronization¶

The two domains of synchronization in OpenCL are work-items in a single work- group and command-queue(s) in a single context. Work-group barriers enable synchronization of work-items in a work-group. Each work-item in a work-group must first execute the barrier before executing any instruction beyond this barrier. Either all of, or none of, the work-items in a work-group must encounter the barrier. A barrier or mem_fence operation does not have global scope, but is relevant only to the local workgroup on which they operate.

There are two types of synchronization between commands in a command- queue:

command-queue barrier - enforces ordering within a single queue. Any resulting changes to memory are available to the following commands in the queue.

events - enforces ordering between, or within, queues. Enqueued commands in OpenCL return an event identifying the command as well as the memory object updated by it. This ensures that following commands waiting on that event see the updated memory objects before they execute.

OpenCL 2.0 provides additional synchronization options. For an overview, see “Atomics and synchronization.”.

Memory Architecture and Access¶

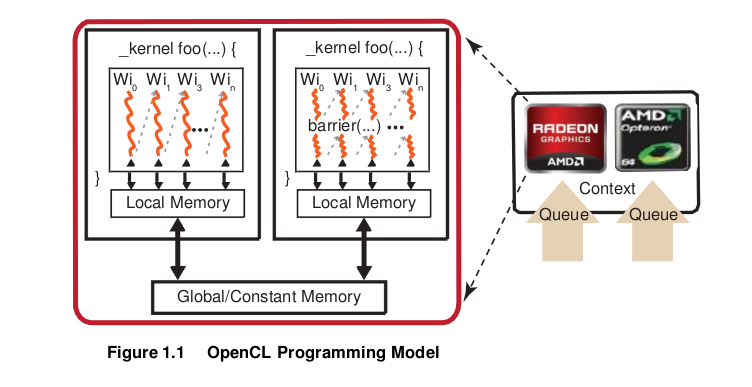

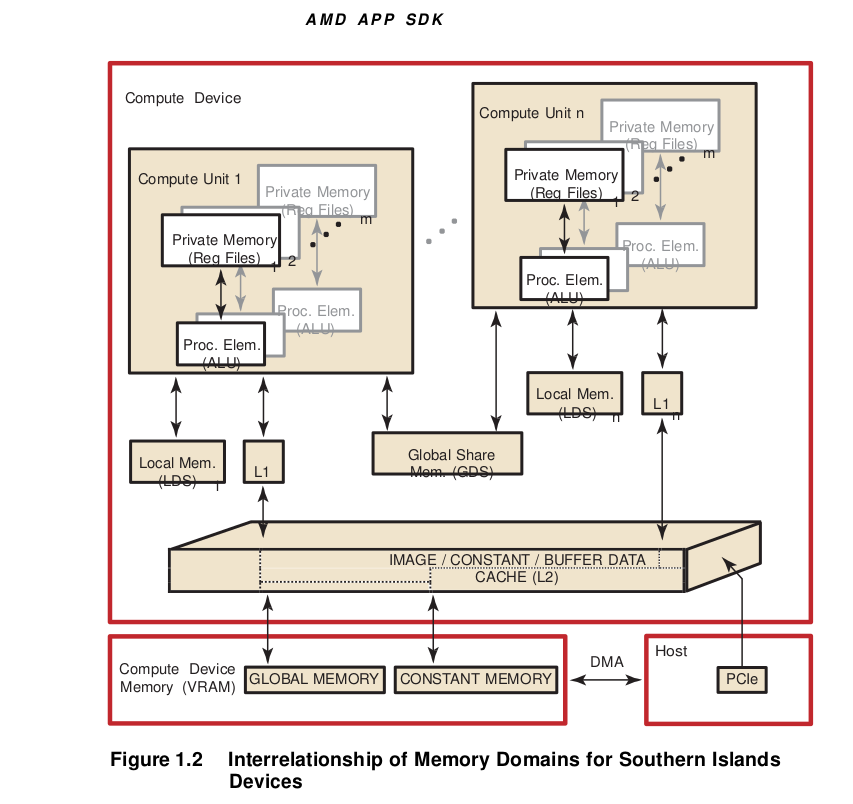

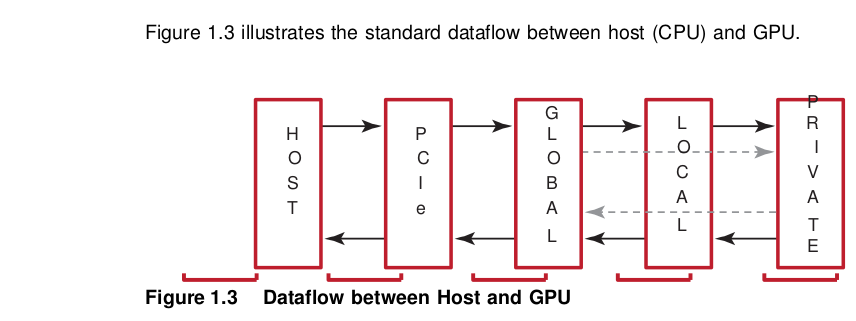

OpenCL has four memory domains: private, local, global, and constant; the AMD Compute Technology system also recognizes host (CPU) and PCI Express® (PCIe® ) memory.

Memory Type |

Description |

|---|---|

private |

Specific to a work-item; it is not visible to other work-items. |

local |

Specific to a work-group; accessible only by work-items belonging to that work-group. |

global |

Accessible to all work-items executing in a context, as well as to the host (read, write, and map commands). |

constant |

Read-only region for host-allocated and -initialized objects that are not changed during kernel execution. |

host (CPU) |

Host-accessible region for an application’s data structures and program data. |

PCIe |

Part of host (CPU) memory accessible from, and modifiable by, the host program and the GPU compute device. Modifying this memory requires synchronization between the GPU compute device and the CPU. |

Table: illustrates the interrelationship of the memories.

There are two ways to copy data from the host to the GPU compute device memory:

Implicitly by using

clEnqueueMapBufferandclEnqueueUnMapMemObject.Explicitly through

clEnqueueReadBuffer,clEnqueueWriteBufferand(clEnqueueReadImage, clEnqueueWriteImage).

When using these interfaces, it is important to consider the amount of copying involved. There is a two-copy processes: between host and PCIe, and between PCIe and GPU compute device.

With proper memory transfer management and the use of system pinned memory (host/CPU memory remapped to the PCIe memory space), copying between host (CPU) memory and PCIe memory can be skipped.

Double copying lowers the overall system memory bandwidth. In GPU compute device programming, pipelining and other techniques help reduce these bottlenecks. See the AMD OpenCL Optimization Reference Guide for more specifics about optimization techniques.

Dataflow in Memory Hierarchy¶

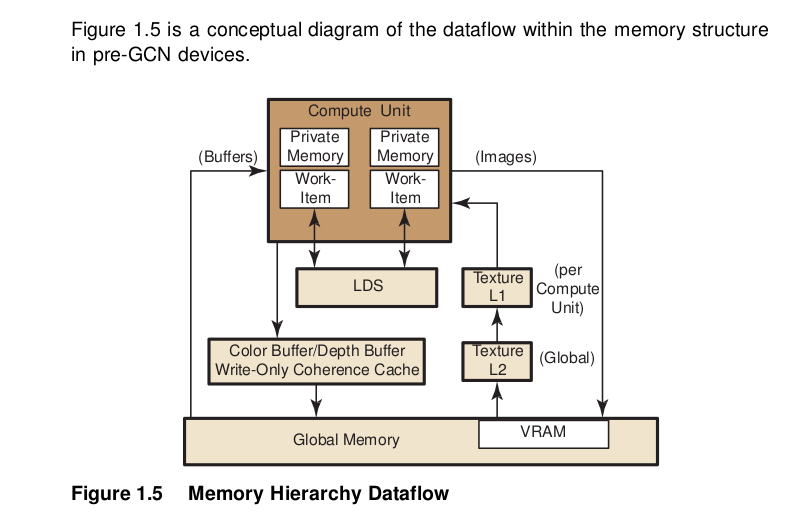

To load data into LDS from global memory, it is read from global memory and placed into the work-item’s registers; then, a store is performed to LDS. Similarly, to store data into global memory, data is read from LDS and placed into the work- item’s registers, then placed into global memory. To make effective use of the LDS, an algorithm must perform many operations on what is transferred between global memory and LDS. It also is possible to load data from a memory buffer directly into LDS, bypassing VGPRs.

LDS atomics are performed in the LDS hardware. (Thus, although ALUs are not directly used for these operations, latency is incurred by the LDS executing this function.) If the algorithm does not require write-to-read reuse (the data is read only), it usually is better to use the image dataflow (see right side of Figure 1.5) because of the cache hierarchy.

Actually, buffer reads may use L1 and L2. When caching is not used for a buffer, reads from that buffer bypass L2. After a buffer read, the line is invalidated; then, on the next read, it is read again (from the same wavefront or from a different clause). After a buffer write, the changed parts of the cache line are written to memory.

Buffers and images are written through the texture L2 cache, but this is flushed immediately after an image write.

In GCN devices, both reads and writes happen through L1 and L2.

The data in private memory is first placed in registers. If more private memory is used than can be placed in registers, or dynamic indexing is used on private arrays, the overflow data is placed (spilled) into scratch memory. Scratch memory is a private subset of global memory, so performance can be dramatically degraded if spilling occurs.

Global memory can be in the high-speed GPU memory (VRAM) or in the host memory, which is accessed by the PCIe bus. A work-item can access global memory either as a buffer or a memory object. Buffer objects are generally read and written directly by the work-items. Data is accessed through the L2 and L1 data caches on the GPU. This limited form of caching provides read coalescing among work-items in a wavefront. Similarly, writes are executed through the texture L2 cache.

Global atomic operations are executed through the texture L2 cache. Atomic instructions that return a value to the kernel are handled similarly to fetch instructions: the kernel must use S_WAITCNT to ensure the results have been written to the destination GPR before using the data.

Memory Access¶

Using local memory (known as local data store, or LDS, as shown in Figure 1.2) typically is an order of magnitude faster than accessing host memory through global memory (VRAM), which is one order of magnitude faster again than PCIe. However, stream cores do not directly access memory; instead, they issue memory requests through dedicated hardware units. When a work-item tries to access memory, the work-item is transferred to the appropriate fetch unit. The work-item then is deactivated until the access unit finishes accessing memory. Meanwhile, other work-items can be active within the compute unit, contributing to better performance. The data fetch units handle three basic types of memory operations: loads, stores, and streaming stores. GPU compute devices can store writes to random memory locations using global buffers.

Global Memory¶

The global memory lets applications read from, and write to, arbitrary locations in memory. When using global memory, such read and write operations from the stream kernel are done using regular GPU compute device instructions with the global memory used as the source or destination for the instruction. The programming interface is similar to load/store operations used with CPU programs, where the relative address in the read/write buffer is specified.

When using a global memory, each work-item can write to an arbitrary location within it. Global memory use a linear layout. If consecutive addresses are written, the compute unit issues a burst write for more efficient memory access. Only read-only buffers, such as constants, are cached.

Image Read/Write¶

Image reads are done by addressing the desired location in the input memory using the fetch unit. The fetch units can process either 1D or 2 D addresses. These addresses can be normalized or un-normalized. Normalized coordinates are between 0.0 and 1.0 (inclusive). For the fetch units to handle 2D addresses and normalized coordinates, pre-allocated memory segments must be bound to the fetch unit so that the correct memory address can be computed. For a single kernel invocation, up to 128 images can be bound at once for reading, and eight for writing. The maximum number of addresses is 8192x8192 for Evergreen and Northern Islands-based devices, 16384x16384 for SI-based products.

Image reads are cached through the texture system (corresponding to the L2 and L1 caches).

Example Programs¶

The following subsections provide simple programming examples with explanatory comments.

First Example: Simple Buffer Write¶

This sample shows a minimalist OpenCL C program that sets a given buffer to some value. It illustrates the basic programming steps with a minimum amount of code. This sample contains no error checks and the code is not generalized. Yet, many simple test programs might look very similar. The entire code for this sample is provided at the end of this section.

The host program must select a platform, which is an abstraction for a given OpenCL implementation. Implementations by multiple vendors can coexist on a host, and the sample uses the first one available.

A device id for a GPU device is requested. A CPU device could be requested by using CL_DEVICE_TYPE_CPU instead. The device can be a physical device, such as a given GPU, or an abstracted device, such as the collection of all CPU cores on the host.

On the selected device, an OpenCL context is created. A context ties together a device, memory buffers related to that device, OpenCL programs, and command queues. Note that buffers related to a device can reside on either the host or the device. Many OpenCL programs have only a single context, program, and command queue.

Before an OpenCL kernel can be launched, its program source is compiled, and a handle to the kernel is created.

A memory buffer is allocated in the context.

The kernel is launched. While it is necessary to specify the global work size, OpenCL determines a good local work size for this device. Since the kernel was launch asynchronously,

clFinish()is used to wait for completion.The data is mapped to the host for examination. Calling clEnqueueMapBuffer ensures the visibility of the buffer on the host, which in this case probably includes a physical transfer. Alternatively, we could use

clEnqueueWriteBuffer(), which requires a pre-allocated host-side buffer.

Example Code 1

//

// Copyright (c) 2010 Advanced Micro Devices, Inc. All rights reserved.

//

// A minimalist OpenCL program.

#include <CL/cl.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#define NWITEMS 512

// A simple memset kernel

const char *source =

"kernel void memset( global uint *dst ) \n"

"{ \n"

" dst[get_global_id(0)] = get_global_id(0); \n"

"} \n";

int main(int argc, char ** argv)

{

// 1. Get a platform.

cl_platform_id platform;

clGetPlatformIDs( 1, &platform, NULL );

// 2. Find a gpu device.

cl_device_id device;

clGetDeviceIDs( platform,

CL_DEVICE_TYPE_GPU,

1,

&device, NULL);

// 3. Create a context and command queue on that device.

cl_context context = clCreateContext( NULL,

1,

&device,

NULL, NULL, NULL);

cl_command_queue queue = clCreateCommandQueue( context,

device,

0, NULL );

// 4. Perform runtime source compilation, and obtain kernel entry point.

cl_program program = clCreateProgramWithSource( context,

1,

&source,

NULL, NULL );

clBuildProgram( program, 1, &device, NULL, NULL, NULL );

cl_kernel kernel = clCreateKernel( program, "memset", NULL );

// 5. Create a data buffer.

cl_mem buffer = clCreateBuffer( context,

CL_MEM_WRITE_ONLY,

NWITEMS * sizeof(cl_uint),

NULL, NULL );

// 6. Launch the kernel. Let OpenCL pick the local work size.

size_t global_work_size = NWITEMS;

clSetKernelArg(kernel, 0, sizeof(buffer), (void*) &buffer);

clEnqueueNDRangeKernel( queue,

kernel,

1,

NULL,

&global_work_size,

NULL,

0,

NULL, NULL);

clFinish( queue );

// 7. Look at the results via synchronous buffer map.

cl_uint *ptr;

ptr = (cl_uint *) clEnqueueMapBuffer( queue,

buffer,

CL_TRUE,

CL_MAP_READ,

0,

NWITEMS * sizeof(cl_uint),

0, NULL, NULL, NULL );

int i;

for(i=0; i < NWITEMS; i++)

printf("%d %d\n", i, ptr[i]);

return 0;

}

Example: SAXPY Function¶

This section provides an introductory sample for beginner-level OpenCL programmers using C++ bindings.

The sample implements the SAXPY function (Y = aX + Y, where X and Y are vectors, and a is a scalar). The full code is reproduced at the end of this section. It uses C++ bindings for OpenCL. These bindings are available in the CL/cl.hpp file in the AMD Compute SDK; they also are downloadable from the Khronos website: http://www.khronos.org/registry/cl

The following steps guide you through this example.

Enable error checking through the exception handling mechanism in the C++ bindings by using the following define.

#define CL ENABLE_EXCEPTIONSThis removes the need to error check after each OpenCL call. If there is an error, the C++ bindings code throw an exception that is caught at the end of the try block, where we can clean up the host memory allocations. In this example, the C++ object representing OpenCL resources (cl::Context, cl::CommandQueue, etc.) are declared as automatic variables, so they do not need to be released. If an OpenCL call returns an error, the error code is defined in the CL/cl.h file.

The kernel is very simple: each work-item, i, does the SAXPY calculation for its corresponding elements

Y[i] = aX[i] + Y[i]. Both X and Y vectors are stored in global memory; X is read-only, Y is read-write.kernel void saxpy(const __global float * X, __global float * Y, const float a) { uint gid = get_global_id(0); Y[gid] = a* X[gid] + Y[gid]; }

List all platforms on the machine, then select one.

cl::Platform::get(&platforms);

Create an OpenCL context on that platform.

cl_context_properties cps[3] = { CL_CONTEXT_PLATFORM, (cl_context_properties)(*iter)(), 0 }; context = cl::Context(CL_DEVICE_TYPE_GPU, cps);

Get OpenCL devices from the context.

devices = context.getInfo<CL_CONTEXT_DEVICES>();

Create an OpenCL command queue.

queue = cl::CommandQueue(context, devices[0]);

Create two buffers, corresponding to the X and Y vectors. Ensure the host- side buffers, pX and pY, are allocated and initialized. The CL_MEM_COPY_HOST_PTR flag instructs the runtime to copy over the contents of the host pointer pX in order to initialize the buffer bufX. The bufX buffer uses the CL_MEM_READ_ONLY flag, while bufY requires the CL_MEM_READ_WRITE flag.

bufX = cl::Buffer(context, CL_MEM_READ_ONLY | CL_MEM_COPY_HOST_PTR, sizeof(cl_float) * length, pX);

Create a program object from the kernel source string, build the program for our devices, and create a kernel object corresponding to the SAXPY kernel. (At this point, it is possible to create multiple kernel objects if there are more than one.)

cl::Program::Sources sources(1, std::make_pair(kernelStr.c_str(), kernelStr.length())); program = cl::Program(context, sources); program.build(devices); kernel = cl::Kernel(program, "saxpy");

Enqueue the kernel for execution on the device (GPU in our example).

Set each argument individually in separate kernel.setArg() calls. The arguments, do not need to be set again for subsequent kernelenqueue calls. Reset only those arguments that are to pass a new value to the kernel. Then, enqueue the kernel to the command queue with the appropriate global and local work sizes.

kernel.setArg(0,bufX); kernel.setArg(1,bufY); kernel.setArg(2,a); queue.enqueueNDRangeKernel(kernel, cl::NDRange(), cl::NDRange(length), cl::NDRange(64));

Read back the results from bufY to the host pointer pY. We will make this a blocking call (using the CL_TRUE argument) since we do not want to proceed before the kernel has finished execution and we have our results back.

queue.enqueueReadBuffer(bufY, CL_TRUE, 0, length * sizeof(cl_float), pY);

Clean up the host resources (pX and pY). OpenCL resources is cleaned up by the C++ bindings support code.

The catch(cl::Error err) block handles exceptions thrown by the C++ bindings code. If there is an OpenCL call error, it prints out the name of the call and the error code (codes are defined in CL/cl.h). If there is a kernel compilation error, the error code is CL_BUILD_PROGRAM_FAILURE, in which case it is necessary to print out the build log.

Example Code 2

#define __CL_ENABLE_EXCEPTIONS

#include <CL/cl.hpp>

#include <string>

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

using std::cout;

using std::cerr;

using std::endl;

using std::string;

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Helper function to print vector elements

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

void printVector(const std::string arrayName,

const cl_float * arrayData,

const unsigned int length)

{

int numElementsToPrint = (256 < length) ? 256 : length;

cout << endl << arrayName << ":" << endl;

for(int i = 0; i < numElementsToPrint; ++i)

cout << arrayData[i] << " ";

cout << endl;

}

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Globals

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

int length = 256;

cl_float * pX = NULL;

cl_float * pY = NULL;

cl_float a = 2.f;

std::vector<cl::Platform> platforms;

cl::Context context;

std::vector<cl::Device> devices;

cl::CommandQueue queue;

cl::Program program;

cl::Kernel kernel;

cl::Buffer bufX;

cl::Buffer bufY;

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// The saxpy kernel

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

string kernelStr =

"__kernel void saxpy(const global float * x,\n"

" __global float * y,\n"

" const float a)\n"

"{\n"

" uint gid = get_global_id(0);\n"

" y[gid] = a* x[gid] + y[gid];\n"

"}\n";

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Allocate and initialize memory on the host

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

void initHost()

{

size_t sizeInBytes = length * sizeof(cl_float);

pX = (cl_float *) malloc(sizeInBytes);

if(pX == NULL)

throw(string("Error: Failed to allocate input memory on host\n"));

pY = (cl_float *) malloc(sizeInBytes);

if(pY == NULL)

throw(string("Error: Failed to allocate input memory on host\n"));

for(int i = 0; i < length; i++)

{

pX[i] = cl_float(i);

pY[i] = cl_float(length-1-i);

}

printVector("X", pX, length);

printVector("Y", pY, length);

}

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Release host memory

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

void cleanupHost()

{

if(pX)

{

free(pX);

pX = NULL;

}

if(pY != NULL)

{

free(pY);

pY = NULL;

}

}

int main(int argc, char * argv[])

{

try

{

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Allocate and initialize memory on the host

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

initHost();

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Find the platform

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

cl::Platform::get(&platforms);

std::vector<cl::Platform>::iterator iter;

for(iter = platforms.begin(); iter != platforms.end(); ++iter)

{

if( !strcmp((*iter).getInfo<CL_PLATFORM_VENDOR>().c_str(), "Advanced Micro Devices, Inc.") )

{

break;

}

}

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Create an OpenCL context

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

cl_context_properties cps[3] = { CL_CONTEXT_PLATFORM,

(cl_context_properties)(*iter)(), 0 };

context = cl::Context(CL_DEVICE_TYPE_GPU, cps);

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Detect OpenCL devices

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

devices = context.getInfo<CL_CONTEXT_DEVICES>();

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Create an OpenCL command queue

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

queue = cl::CommandQueue(context, devices[0]);

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Create OpenCL memory buffers

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

bufX = cl::Buffer(context,

CL_MEM_READ_ONLY | CL_MEM_COPY_HOST_PTR,

sizeof(cl_float) * length,

pX);

bufY = cl::Buffer(context,

CL_MEM_READ_WRITE | CL_MEM_COPY_HOST_PTR,

sizeof(cl_float) * length,

pY);

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Load CL file, build CL program object, create CL kernel object

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

cl::Program::Sources sources(1, std::make_pair(kernelStr.c_str(),

kernelStr.length()));

program = cl::Program(context, sources);

program.build(devices);

kernel = cl::Kernel(program, "saxpy");

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Set the arguments that will be used for kernel execution

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

kernel.setArg(0, bufX);

kernel.setArg(1, bufY);

kernel.setArg(2, a);

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Enqueue the kernel to the queue

// with appropriate global and local work sizes

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

queue.enqueueNDRangeKernel(kernel, cl::NDRange(),

cl::NDRange(length), cl::NDRange(64));

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Enqueue blocking call to read back buffer Y

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

queue.enqueueReadBuffer(bufY, CL_TRUE, 0, length *

sizeof(cl_float), pY);

printVector("Y", pY, length);

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Release host resources

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

cleanupHost();

}

catch (cl::Error err)

{

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

// Catch OpenCL errors and print log if it is a build error

/////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

cerr << "ERROR: " << err.what() << "(" << err.err() << ")" << endl;

if (err.err() == CL_BUILD_PROGRAM_FAILURE)

{

string str = program.getBuildInfo<CL_PROGRAM_BUILD_LOG>(devices[0]);

cout << "Program Info: " << str << endl;

}

cleanupHost();

}

catch(string msg)

{

cerr << "Exception caught in main(): " << msg << endl;

cleanupHost();

}

}

Example: Parallel Min( ) Function¶

This medium-complexity sample shows how to implement an efficient parallel min() function.

The code is written so that it performs very well on either CPU or GPU. The number of threads launched depends on how many hardware processors are available. Each thread walks the source buffer, using a device-optimal access pattern selected at runtime. A multi-stage reduction using local and global atomics produces the single result value.

The sample includes a number of programming techniques useful for simple tests. Only minimal error checking and resource tear-down is used.

Runtime Code –

The source memory buffer is allocated, and initialized with a random pattern. Also, the actual min() value for this data set is serially computed, in order to later verify the parallel result.

The compiler is instructed to dump the intermediate IL and ISA files for further analysis.

The main section of the code, including device setup, CL data buffer creation, and code compilation, is executed for each device, in this case for CPU and GPU. Since the source memory buffer exists on the host, it is shared. All other resources are device specific.

The global work size is computed for each device. A simple heuristic is used to ensure an optimal number of threads on each device. For the CPU, a given CL implementation can translate one work-item per CL compute unit into one thread per CPU core.

On the GPU, an initial multiple of the wavefront size is used, which is adjusted to ensure even divisibility of the input data over all threads. The value of 7 is a minimum value to keep all independent hardware units of the compute units busy, and to provide a minimum amount of memory latency hiding for a kernel with little ALU activity.

After the kernels are built, the code prints errors that occurred during kernel compilation and linking.

The main loop is set up so that the measured timing reflects the actual kernel performance. If a sufficiently large NLOOPS is chosen, effects from kernel launch time and delayed buffer copies to the device by the CL runtime are minimized. Note that while only a single clFinish() is executed at the end of the timing run, the two kernels are always linked using an event to ensure serial execution.

The bandwidth is expressed as “number of input bytes processed.” For high- end graphics cards, the bandwidth of this algorithm is about an order of magnitude higher than that of the CPU, due to the parallelized memory subsystem of the graphics card.

The results then are checked against the comparison value. This also establishes that the result is the same on both CPU and GPU, which can serve as the first verification test for newly written kernel code.

Note the use of the debug buffer to obtain some runtime variables. Debug buffers also can be used to create short execution traces for each thread, assuming the device has enough memory.

You can use the Timer.cpp and Timer.h files from the TransferOverlap sample, which is in the SDK samples.

Kernel Code –

The code uses four-component vectors (uint4) so the compiler can identify concurrent execution paths as often as possible. On the GPU, this can be used to further optimize memory accesses and distribution across ALUs. On the CPU, it can be used to enable SSE like execution.

The kernel sets up a memory access pattern based on the device. For the CPU, the source buffer is chopped into continuous buffers: one per thread. Each CPU thread serially walks through its buffer portion, which results in good cache and prefetch behavior for each core.

On the GPU, each thread walks the source buffer using a stride of the total number of threads. As many threads are executed in parallel, the result is a maximally coalesced memory pattern requested from the memory back-end. For example, if each compute unit has 16 physical processors, 16 uint4 requests are produced in parallel, per clock, for a total of 256 bytes per clock.

The kernel code uses a reduction consisting of three stages: global to private,private to local, which is flushed to global, and finally global to global. In the first loop, each thread walks global memory, and reduces all values into a min value in private memory (typically, a register). This is the bulk of the work, and is mainly bound by global memory bandwidth. The subsequent reduction stages are brief in comparison.

Next, all per-thread minimum values inside the work-group are reduced to a local value, using an atomic operation. Access to the local value is serialized; however, the number of these operations is very small compared to the work of the previous reduction stage. The threads within a work-group are synchronized through a local barrier(). The reduced min value is stored in global memory.

After all work-groups are finished, a second kernel reduces all work-group values into a single value in global memory, using an atomic operation. This is a minor contributor to the overall runtime.

Example Code 3

//

// Copyright (c) 2010 Advanced Micro Devices, Inc. All rights reserved.

//

#include <CL/cl.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <time.h>

#include "Timer.h"

#define NDEVS 1

// A parallel min() kernel that works well on CPU and GPU

const char *kernel_source =

" \n"

"#pragma OPENCL EXTENSION cl_khr_local_int32_extended_atomics : enable \n"

"#pragma OPENCL EXTENSION cl_khr_global_int32_extended_atomics : enable \n"

" \n"

"// 9. The source buffer is accessed as 4-vectors. \n"

"__kernel void minp(__global uint4 *src, \n"

" __global uint *gmin, \n"

" __local uint *lmin, \n"

" __global uint *dbg, \n"

" int nitems, \n"

" uint dev ) \n"

"{ \n"

" \n"

" // 10. Set up global memory access pattern. \n"

" \n"

" uint count = ( nitems / 4 ) / get_global_size(0); \n"

" uint idx = (dev == 0) ? get_global_id(0) * count \n"

" : get_global_id(0); \n"

" uint stride = (dev == 0) ? 1 : get_global_size(0); \n"

" uint pmin = (uint) -1; \n"

" // 11. First, compute private min, for this work-item. \n"

" for( int n=0; n < count; n++, idx += stride ) \n"

" { \n"

" pmin = min( pmin, src[idx].x ); \n"

" pmin = min( pmin, src[idx].y ); \n"

" pmin = min( pmin, src[idx].z ); \n"

" pmin = min( pmin, src[idx].w ); \n"

" } \n"

" \n"

" // 12. Reduce min values inside work-group. \n"

" if( get_local_id(0) == 0 ) \n"

" lmin[0] = (uint) -1; \n"

" barrier( CLK_LOCAL_MEM_FENCE ); \n"

" (void) atom_min( lmin, pmin ); \n"

" barrier( CLK_LOCAL_MEM_FENCE ); \n"

" // Write out to __global. \n"

" if( get_local_id(0) == 0 ) \n"

" gmin[ get_group_id(0) ] = lmin[0]; \n"

" // Dump some debug information. \n"

" if( get_global_id(0) == 0 ) \n"

" { \n"

" dbg[0] = get_num_groups(0); \n"

" dbg[1] = get_global_size(0); \n"

" dbg[2] = count; \n"

" dbg[3] = stride; \n"

" } \n"

"} \n"

" \n"

"// 13. Reduce work-group min values from __global to __global. \n"

"kernel void reduce(__global uint4 *src, \n"

" __global uint *gmin ) \n"

"{ \n"

" (void) atom_min( gmin, gmin[get_global_id(0)] ); \n"

"}; \n";

int main(int argc, char ** argv)

{

cl_platform_id platform;

int dev, nw;

cl_device_type devs[NDEVS] = { CL_DEVICE_TYPE_GPU };

cl_uint *src_ptr;

unsigned int num_src_items = 4096*4096;

// 1. quick & dirty MWC random init of source buffer.

// Random seed (portable).

time_t ltime;

time(<ime);

src_ptr = (cl_uint *) malloc( num_src_items * sizeof(cl_uint) );

cl_uint a = (cl_uint) ltime, b = (cl_uint) ltime;

cl_uint min = (cl_uint) -1;

// Do serial computation of min() for result verification.

for( int i=0; i < num_src_items; i++ )

{

src_ptr[i] = (cl_uint) (b = ( a * ( b & 65535 )) + ( b >> 16 ));

min = src_ptr[i] < min ? src_ptr[i] : min;

}

// Get a platform.

clGetPlatformIDs( 1, &platform, NULL );

// 3. Iterate over devices.

for(dev=0; dev < NDEVS; dev++)

{

cl_device_id device;

cl_context context;

cl_command_queue queue;

cl_program program;

cl_kernel minp;

cl_kernel reduce;

cl_mem src_buf;

cl_mem dst_buf;

cl_mem dbg_buf;

cl_uint *dst_ptr,

*dbg_ptr;

printf("\n%s: ", dev == 0 ? "CPU" : "GPU");

// Find the device.

clGetDeviceIDs( platform,

devs[dev],

1,

&device,

NULL);

// 4. Compute work sizes.

cl_uint compute_units;

size_t global_work_size;

size_t local_work_size;

size_t num_groups;

clGetDeviceInfo( device,

CL_DEVICE_MAX_COMPUTE_UNITS,

sizeof(cl_uint),

&compute_units,

NULL);

if( devs[dev] == CL_DEVICE_TYPE_CPU )

{

global_work_size = compute_units * 1; // 1 thread per core

local_work_size = 1;

}

else

{

cl_uint ws = 64;

global_work_size = compute_units * 7 * ws; // 7 wavefronts per SIMD

while( (num_src_items / 4) % global_work_size != 0 )

global_work_size += ws;

local_work_size = ws;

}

num_groups = global_work_size / local_work_size;

// Create a context and command queue on that device.

context = clCreateContext( NULL,

1,

&device,

NULL, NULL, NULL);

queue = clCreateCommandQueue( context,

device,

0,

NULL);

// Minimal error check.

if( queue == NULL )

{

printf("Compute device setup failed\n");

return(-1);

}

// Perform runtime source compilation, and obtain kernel entry point.

program = clCreateProgramWithSource( context,

1,

&kernel_source,

NULL, NULL );

//Tell compiler to dump intermediate .il and .isa GPU files.

cl_int ret = clBuildProgram( program,

1,

&device,

"-save-temps",

NULL, NULL );

// 5. Print compiler error messages

if(ret != CL_SUCCESS)

{

printf("clBuildProgram failed: %d\n", ret);

char buf[0x10000];

clGetProgramBuildInfo( program,

device,

CL_PROGRAM_BUILD_LOG,

0x10000,

buf,

NULL);

printf("\n%s\n", buf);

return(-1);

}

minp = clCreateKernel( program, "minp", NULL );

reduce = clCreateKernel( program, "reduce", NULL );

// Create input, output and debug buffers.

src_buf = clCreateBuffer( context,

CL_MEM_READ_ONLY | CL_MEM_COPY_HOST_PTR,

num_src_items * sizeof(cl_uint),

src_ptr,

NULL );

dst_buf = clCreateBuffer( context,

CL_MEM_READ_WRITE,

num_groups * sizeof(cl_uint),

NULL, NULL );

dbg_buf = clCreateBuffer( context,

CL_MEM_WRITE_ONLY,

global_work_size * sizeof(cl_uint),

NULL, NULL );

clSetKernelArg(minp, 0, sizeof(void *), (void*) &src_buf);

clSetKernelArg(minp, 1, sizeof(void *), (void*) &dst_buf);

clSetKernelArg(minp, 2, 1*sizeof(cl_uint), (void*) NULL);

clSetKernelArg(minp, 3, sizeof(void *), (void*) &dbg_buf);

clSetKernelArg(minp, 4, sizeof(num_src_items), (void*) &num_src_items);

clSetKernelArg(minp, 5, sizeof(dev), (void*) &dev);

clSetKernelArg(reduce, 0, sizeof(void *), (void*) &src_buf);

clSetKernelArg(reduce, 1, sizeof(void *), (void*) &dst_buf);

CPerfCounter t;

t.Reset();

t.Start();

// 6. Main timing loop.

#define NLOOPS 500

cl_event ev;

int nloops = NLOOPS;

while(nloops--)

{

clEnqueueNDRangeKernel( queue,

minp,

1,

NULL,

&global_work_size,

&local_work_size,

0,

NULL,

&ev);

clEnqueueNDRangeKernel( queue,

reduce,

1,

NULL,

&num_groups,

NULL,

1,

&ev,

NULL);

}

clFinish( queue );

t.Stop();

printf("B/W %.2f GB/sec, ", ((float) num_src_items * sizeof(cl_uint) * NLOOPS) / t.GetElapsedTime() / 1e9 );

// 7. Look at the results via synchronous buffer map.

dst_ptr = (cl_uint *) clEnqueueMapBuffer( queue,

dst_buf,

CL_TRUE,

CL_MAP_READ,

0,

num_groups * sizeof(cl_uint),

0,

NULL, NULL, NULL );

dbg_ptr = (cl_uint *) clEnqueueMapBuffer( queue,

dbg_buf,

CL_TRUE,

CL_MAP_READ,

0,

global_work_size * sizeof(cl_uint),

0,

NULL, NULL, NULL );

// 8. Print some debug info.

printf("%d groups, %d threads, count %d, stride %d\n", dbg_ptr[0], dbg_ptr[1], dbg_ptr[2], dbg_ptr[3] );

if( dst_ptr[0] == min )

printf("result correct\n");

else

printf("result INcorrect\n");

}

printf("\n");

return 0;

}

AMD Implementation¶

The AMD ROCm Implementation of OpenCL¶

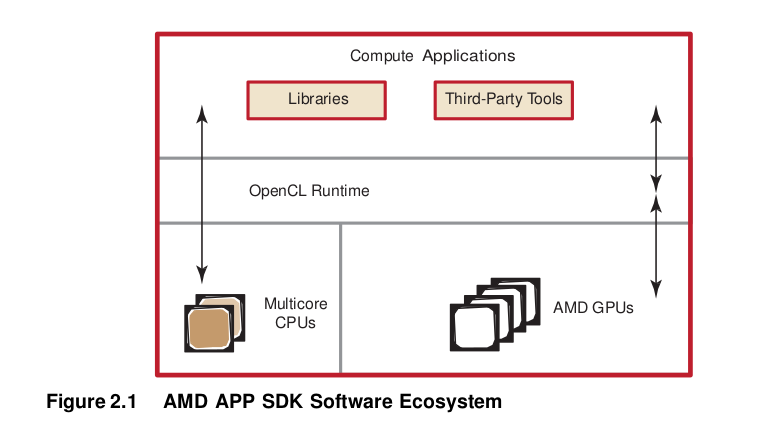

ROCm OpenCL runtime harnesses the tremendous processing power of GPUs for high- performance, data-parallel computing in a wide range of applications. The AMD system includes a software stack, AMD GPUs, and AMD multicore CPUs.

Figure 2.1 illustrates the relationship of the ROCm OpenCL components.

The AMD ROCm software stack provides end-users and developers with a complete, flexible suite of tools to leverage the processing power in AMD GPUs. AMD ROCm software embraces open-systems, open-platform standards. The AMD Accelerated Parallel Processing Technology open platform strategy enables AMD technology partners to develop and provide third-party development tools.

The software includes the following components:

OpenCL compiler and runtime

Debugging and Performance Profiling Tools – AMD CodeXL.

Performance Libraries – clMath and other OpenCL accelerated libraries for optimized NDRange-specific algorithms.

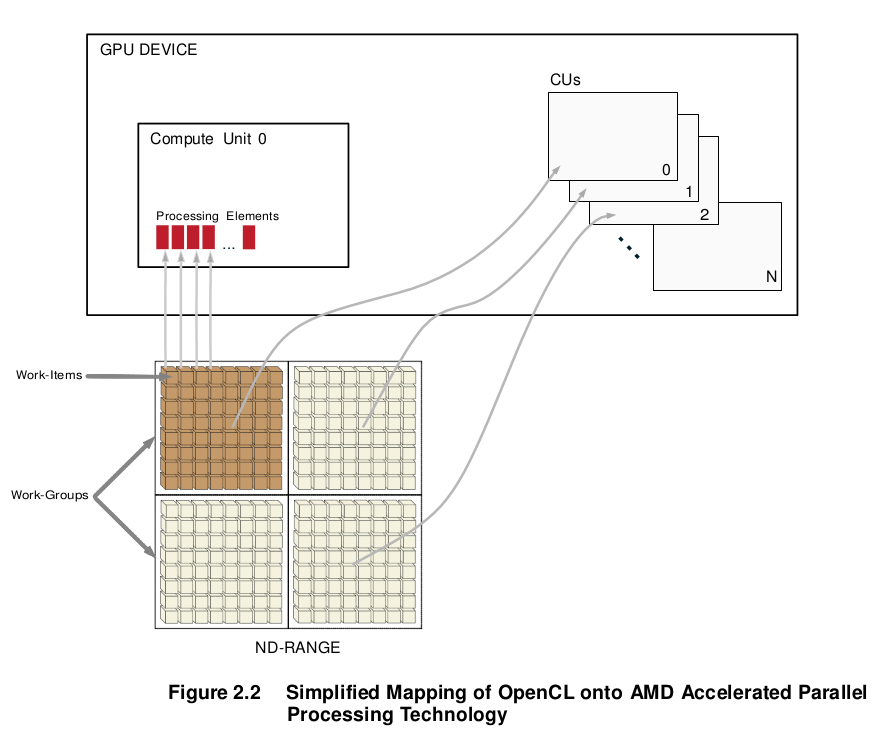

The latest generations of AMD GPUs use unified shader architectures capable of running different kernel types interleaved on the same hardware.Programmable GPU compute devices execute various user-developed programs,known to graphics programmers as shaders and to compute programmers as kernels. These GPU compute devices can execute non-graphics functions using a data-parallel programming model that maps executions onto compute units. Each compute unit contains one (pre-GCN devices) or more (GCN devices) vector (SIMD) units. In this programming model, known as AMD Accelerated Parallel Processing Technology, arrays of input data elements stored in memory are accessed by a number of compute units.

Each instance of a kernel running on a compute unit is called a work-item. Work- items are mapped to an n-dimensional index space, called an NDRange.

The GPU schedules the range of work-items onto a group of processing elements, until all work-items have been processed. Subsequent kernels then can be executed, until the application completes. A simplified view of the AMD Accelerated Parallel Processing Technology programming model and the mapping of work-items to processing elements is shown in Figure 2.2.

Work-groups are assigned to CUs. All work-items of a work-group can be processed only by the processing elements of a single CU. A processing element can process only one work-item at a time; however, a CU can process multiple work-groups.

Note that in OpenCL 2.0, the work-groups are not required to divide evenly into the NDRange.

OpenCL maps the total number of work-items to be launched onto an n- dimensional grid (ND-Range). The developer can specify how to divide these items into work-groups. AMD GPUs execute on wavefronts (groups of work-items executed in lock-step in a compute unit); there is an integer number of wavefronts in each work-group. Thus, as shown in Figure 2.3, hardware that schedules work-items for execution in the AMD Accelerated Parallel Processing Technology environment includes the intermediate step of specifying wavefronts within a work-group. This permits achieving maximum performance on AMD GPUs. For a more detailed discussion of wavefronts.

Work-Item Processing¶

All processing elements within a vector unit execute the same instruction in each cycle. For a typical instruction, 16 processing elements execute one instruction for 64 work items over 4 cycles. The block of work-items that are executed together is called a wavefront. For example, on the AMD Radeon™ HD 290X

compute device, the 16 processing elements within each vector unit execute the same instruction for four cycles, which effectively appears as a 64-wide compute unit in execution width.

The size of wavefronts can differ on different GPU compute devices. For example, some of the low-end and older GPUs, such as the AMD Radeon™ HD 54XX series graphics cards, have a wavefront size of 32 work-items. Higher-end and newer AMD GPUs have a wavefront size of 64 work-items.

Compute units operate independently of each other, so it is possible for different compute units to execute different instructions. It is also possible for different vector units within a compute unit to execute different instructions.

Before discussing flow control, it is necessary to clarify the relationship of a wavefront to a work-group. If a user defines a work-group, it consists of one or more wavefronts. A wavefront is a hardware thread with its own program counter; it is capable of following control flow independently of other wavefronts. A wavefront consists of 64 or fewer work-items. The mapping is based on a linear work-item order. On a device with a wavefront size of 64, work-items 0-63 map to wavefront 0, work items 64-127 map to wavefront 1, etc. For optimum hardware usage, an integer multiple of 64 work-items is recommended.

work-Item Creation¶

For each work-group, the GPU compute device spawns the required number of wavefronts on a single compute unit. If there are non-active work-items within a wavefront, the processing elements that would have been mapped to those work- items are idle. An example is a work-group that is a non-multiple of a wavefront size.

Flow Control¶

Flow control, such as branching, is achieved by combining all necessary paths as a wavefront. If work-items within a wavefront diverge, all paths are executed serially. For example, if a work-item contains a branch with two paths, the wavefront first executes one path, then the second path. The total time to execute the branch is the sum of each path time. An important point is that even if only one work-item in a wavefront diverges, the rest of the work-items in the wavefront execute the branch. The number of work-items that must be executed during a branch is called the branch granularity. On AMD hardware, the branch granularity is the same as the number of work-items in a wavefront.

Masking of wavefronts is effected by constructs such as:

if(x)

{

. //items within these braces = A

.

.

}

else

{

. //items within these braces = B

.

.

}

The wavefront mask is set true for lanes (elements/items) in which x is true, then execute A. The mask then is inverted, and B is executed.

Example 1: If two branches, A and B, take the same amount of time t to execute over a wavefront, the total time of execution, if any work-item diverges, is 2t.

Loops execute in a similar fashion, where the wavefront occupies a compute unit as long as there is at least one work-item in the wavefront still being processed. Thus, the total execution time for the wavefront is determined by the work-item with the longest execution time.

Example 2: If t is the time it takes to execute a single iteration of a loop; and within a wavefront all work-items execute the loop one time, except for a single work-item that executes the loop 100 times, the time it takes to execute that entire wavefront is 100t.

Hardware Overview for GCN Devices¶

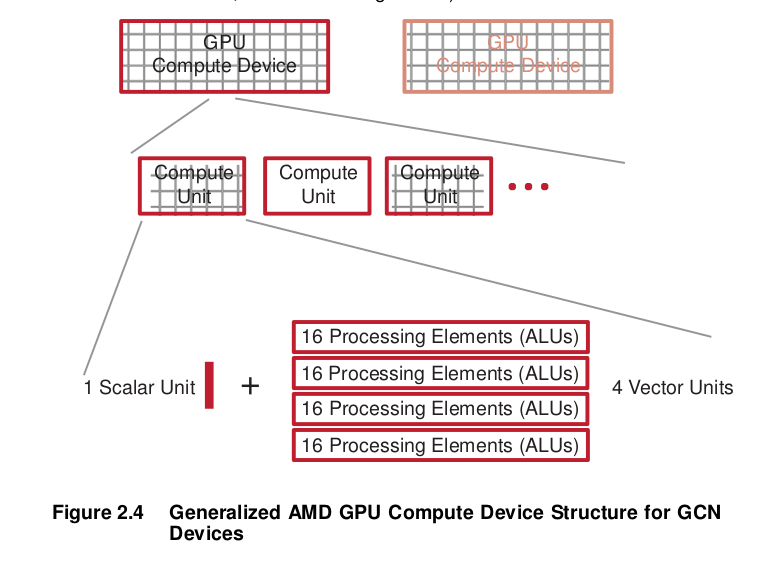

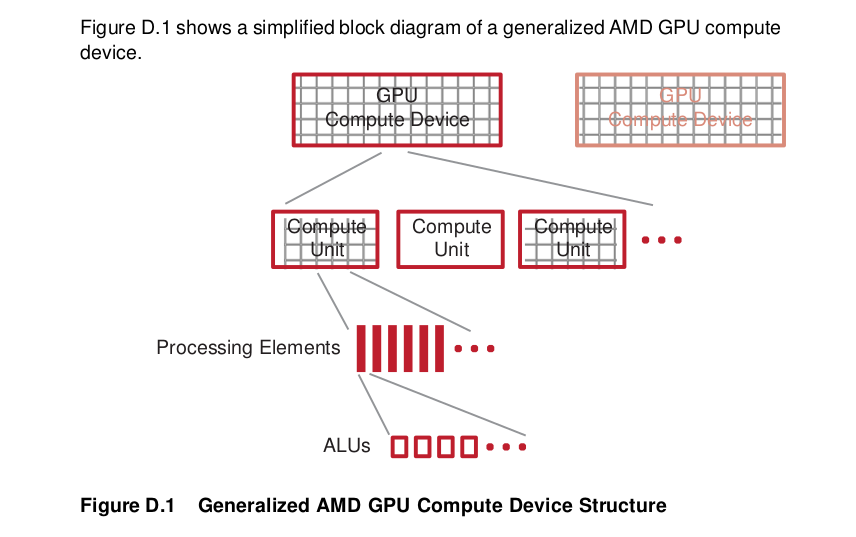

A general OpenCL device comprises compute units (CUs), each of which has sub-modules that ultimately have ALUs. A work-item (or SPMD kernel instance) executes on an ALU, as shown in Figure 2.4).

In GCN devices, each CU includes one Scalar Unit and four Vector (SIMD) units, each of which contains an array of 16 processing elements (PEs). Each PE contains one ALU. Each SIMD unit simultaneously executes a single operation across 16 work items, but each can be working on a separate wavefront.

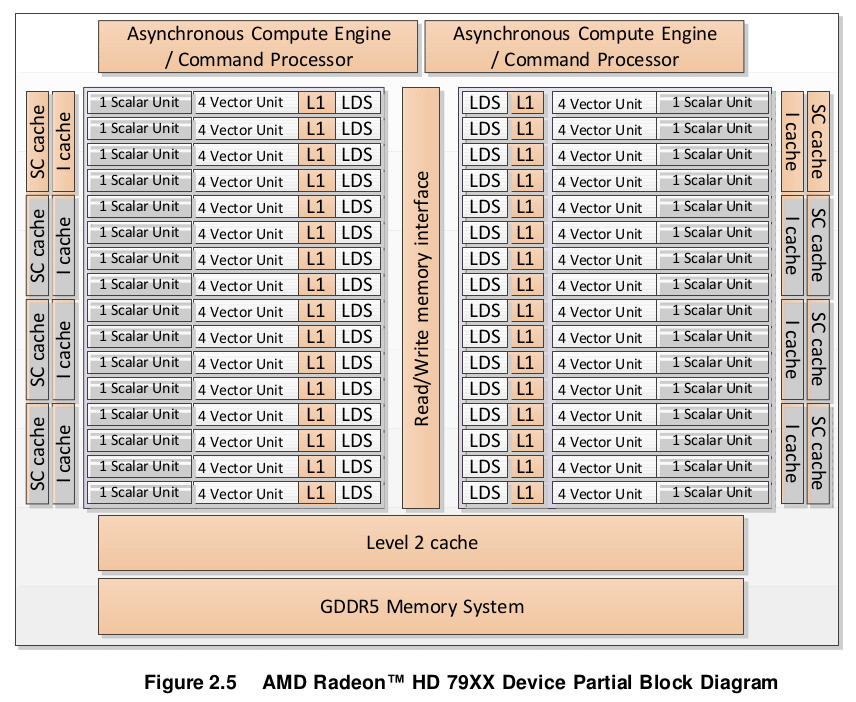

For example, for the AMD Radeon™ HD 79XX devices each of the 32 CUs has one Scalar Unit and four Vector Units. Figure 2.5 shows only two compute engines/command processors of the array that comprises the compute device of the AMD Radeon™ HD 79XX family.

In Figure 2.5, there are two command processors, which can process two command queues concurrently. The Scalar Unit, Vector Unit, Level 1 data cache (L1), and Local Data Share (LDS) are the components of one compute unit, of which there are 32. The scalar (SC) cache is the scalar unit data cache, and the Level 2 cache consists of instructions and data.

On GCN devices, the instruction stream contains both scalar and vector instructions. On each cycle, it selects a scalar instruction and a vector instruction (as well as a memory operation and a branch operation, if available); it issues one to the scalar unit, the other to the vector unit; this takes four cycles to issue over the four vector cores (the same four cycles over which the 16 units execute 64 work-items).

The Asynchronous Compute Engines (ACEs) manage the CUs; a graphics command processor handles graphics shaders and fixed-function hardware.

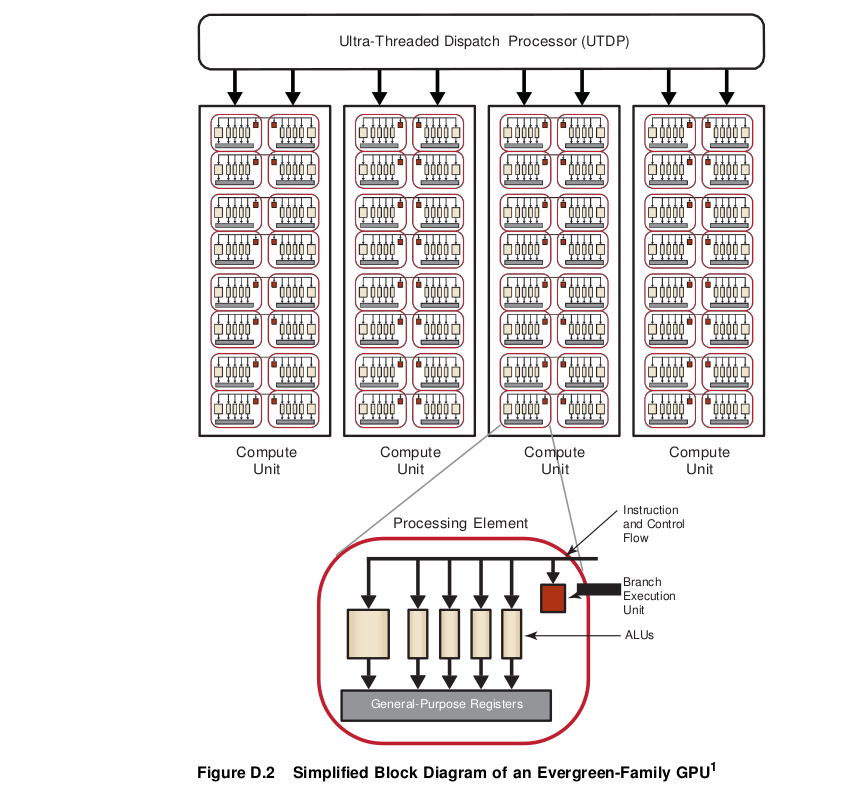

Key differences between pre-GCN and GCN devices¶

In pre-GCN devices (for a hardware overview, see Appendix D, “Hardware overview of pre-GCN devices.”), each compute unit consists of a single vector unit, each containing up to 16 processing elements. Each processing element, which contains 4 or 5 ALUs, could execute bundles of 4 or 5 independent instructions co-issued in a VLIW (Very Long Instruction Word) format. All the processing elements within a vector unit execute a single wavefront (a group of 64 work items). If operations within a wavefront contain dependencies, they cannot be scheduled in the same clock cycle, leaving some ALUs un-utilized. In such cases, some processing elements (and hence, vector units) remain under- utilized.

In GCN devices, the CUs are arranged in four vector unit arrays consisting of 16 processing elements each. Each of these arrays executes a single instruction across each lane for each block of 16 work-items. That instruction is repeated over four cycles to make the 64-element vector called a wavefront.

Thus, in GCN devices, the four vector units within a CU can operate on four different wavefronts. If operations within a wavefront include dependencies, independent operations from different wavefronts can be selected to be assigned to a single vector unit to be executed in parallel every cycle.

GCN-based GPUs have 32KB of dedicated L1 instruction cache. A single instruction cache instance serves up to 4 CUs (depending upon the architecture family and device), with each CU holding up to 40 wavefronts. As each wavefront includes its own program counter, a single instruction cache unit may serve up to 160 wavefronts with each executing a different instruction in the program.

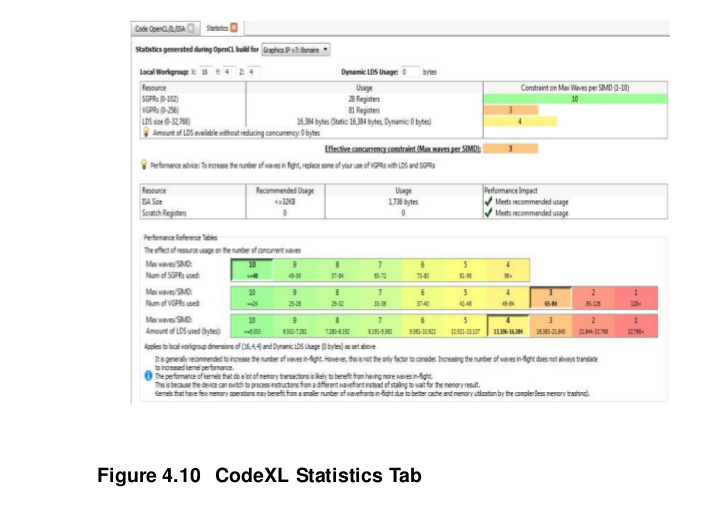

Note: If the program is larger than 32KB, the L1-L2 cache trashing can inhibit performance. The size of the ISA can be determined by using the CodeXL analysis mode, under the Statistics tab. For information about how to use CodeXL, see Chapter 4.

Key differences between Southern Islands, Sea Islands, and Volcanic Islands families¶

The number of Asynchronous Compute Engines (ACEs) and CUs in an AMD GCN family GPU, and the way they are structured, vary with the GCN device family, as well as with the device designations within the family.

The ACEs are responsible for managing the CUs and for scheduling and resource allocation of the compute tasks (but not of the graphics shader tasks). The ACEs operate independently; the greater the number of ACEs, the greater is the performance. Each ACE fetches commands from cache or memory, and

creates task queues to be scheduled for execution on the CUs depending on their priority and on the availability of resources.

Each ACE contains up to eight hardware queues and, together with the graphics command processor, allows up to nine independent vector instructions to be executed per clock cycle. Some of these queues are not available for use by OpenCL.

Devices in the Southern Islands families typically have two ACEs. The ACE engines on the Southern Islands families are single-threaded, which means that they contain two hardware queues.

Devices in the Sea Islands and Volcanic Islands families contain between four and eight ACEs, and are multi-threaded (thereby supporting more hardware queues) so they offer more performance. For example, the AMD Radeon™ R9 290X devices, in the VI family contain 8 ACEs and 44 CUs.

A note on hardware queues¶

A hardware queue can be thought of as a GPU entry point. The GPU can process kernels from several compute queues concurrently. All hardware queues ultimately share the same compute cores. The use of multiple hardware queues is beneficial when launching small kernels that do not fully saturate the GPU. For example, the AMD Radeon™ HD 290X compute device can execute up to 112,640 threads concurrently. The GPU can execute two kernels each spawning 56320 threads (assuming fully occupancy) twice as fast if launched concurrently through two hardware queues than serially through a single hardware queue.

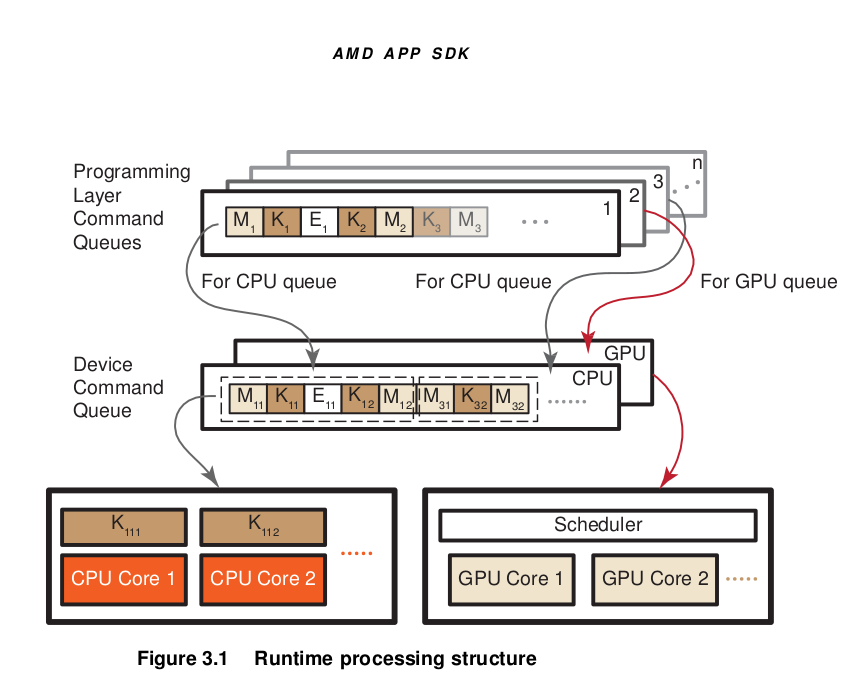

An OpenCL queue is assigned to a hardware queue on creation time. The hardware queue is selected according to the creation order of the OpenCL queue within an OpenCL context. If the GPU supports K hardware queues, the Nth created OpenCL queue will be assigned to the (N mod K) hardware queue. The number of compute queues can be limited by specifying the GPU_NUM_COMPUTE_RINGS environment variable.

Communication Between Host and the GPU Compute Device¶

The following subsections discuss the communication between the host (CPU) and the GPU in a compute device. This includes an overview of the PCIe bus, processing API calls, and DMA transfers.

Communication and data transfers between the system and the GPU compute device occur on the PCIe channel. AMD graphics cards use PCIe 2.0 x16 (second generation, 16 lanes). Generation 1 x16 has a theoretical maximum throughput of 4 GBps in each direction. Generation 2 x16 doubles the throughput to 8 GBps in each direction. Southern Islands AMD GPUs support PCIe 3.0 with a theoretical peak performance of 16 GBps. Actual transfer performance is CPU and chipset dependent.

Transfers from the system to the GPU compute device are done either by the command processor or by the DMA engine. The GPU compute device also can

read and write system memory directly from the compute unit through kernel instructions over the PCIe bus.

Processing API Calls: The Command Processor¶

The host application does not interact with the GPU compute device directly. A driver layer translates and issues commands to the hardware on behalf of the application.

Most commands to the GPU compute device are buffered in a command queue on the host side. The queue of commands is sent to, and processed by, the GPU compute device. There is no guarantee as to when commands from the command queue are executed, only that they are executed in order.

Command queue elements include:

Kernel execution calls

Kernels

Constants

Transfers between device and host

DMA Transfers¶

Certain memory transfer calls use the DMA engine. To properly leverage the DMA engine, make the associated OpenCL data transfer calls. See the AMD OpenCL Optimization Reference Guide for more information.

Direct Memory Access (DMA) memory transfers can be executed separately from the command queue using the DMA engine on the GPU compute device. DMA calls are executed immediately; and the order of DMA calls and command queue flushes is guaranteed.

DMA transfers can occur asynchronously. This means that a DMA transfer is executed concurrently with other system or GPU compute operations when there are no dependencies. However, data is not guaranteed to be ready until the DMA engine signals that the event or transfer is completed. The application can use OpenCL to query the hardware for DMA event completion. If used carefully, DMA transfers are another source of parallelization.

All GCN devices have two DMA engines that can perform bidirectional transfers over the PCIe bus with multiple queues created in consecutive order, since each DMA engine is assigned to an odd or an even queue correspondingly.

Masking Visible Devices¶

By default, OpenCL applications are exposed to all GPUs installed in the system; this allows applications to use multiple GPUs to run the compute task.

In some cases, the user might want to mask the visibility of the GPUs seen by the OpenCL application. One example is to dedicate one GPU for regular

graphics operations and the other three (in a four-GPU system) for Compute. To do that, set the GPU_DEVICE_ORDINAL environment parameter, which is a comma- separated list variable:

Under Windows: set GPU_DEVICE_ORDINAL=1,2,3

Under Linux: export GPU_DEVICE_ORDINAL=1,2,3

Another example is a system with eight GPUs, where two distinct OpenCL applications are running at the same time. The administrator might want to set GPU_DEVICE_ORDINAL to 0,1,2,3 for the first application, and 4,5,6,7 for the second application; thus, partitioning the available GPUs so that both applications can run at the same time.

Wavefront Scheduling¶

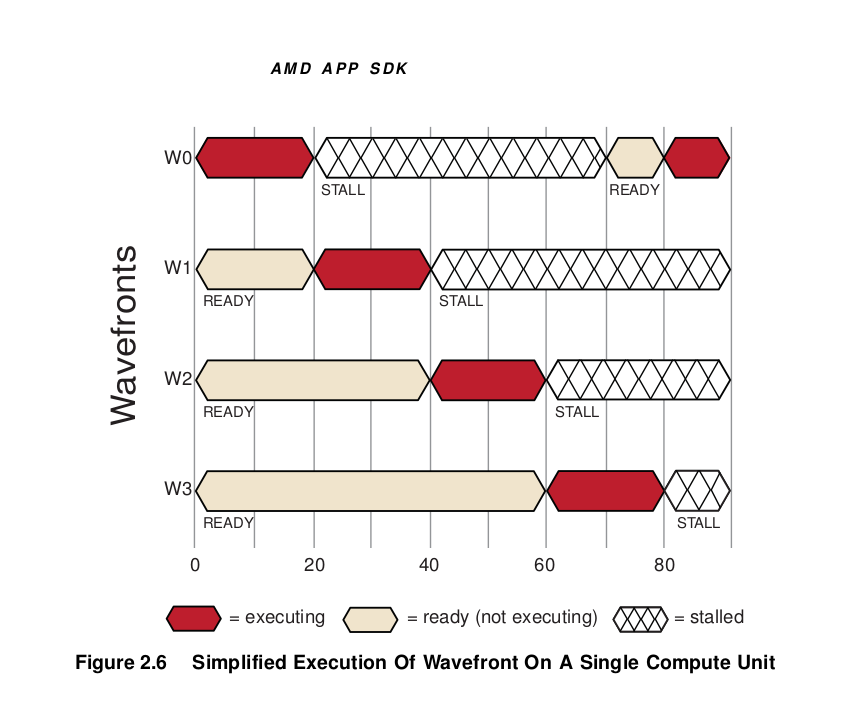

GPU compute devices are very efficient at parallelizing large numbers of work- items in a manner transparent to the application. Each GPU compute device uses the large number of wavefronts to hide memory access latencies by having the resource scheduler switch the active wavefront in a given compute unit whenever the current wavefront is waiting for a memory access to complete. Hiding memory access latencies requires that each work-item contain a large number of ALU operations per memory load/store.

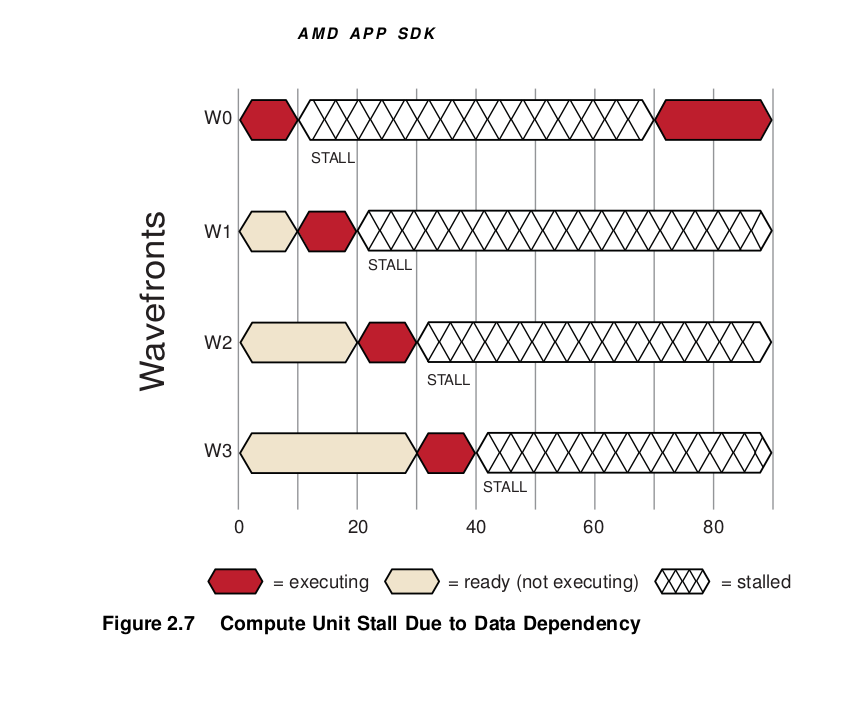

Figure 2.6 shows the timing of a simplified execution of wavefronts in a single compute unit. At time 0, the wavefronts are queued and waiting for execution. In this example, only four wavefronts (T0…T3) are scheduled for the compute unit. The hardware limit for the number of active wavefront is dependent on the resource usage (such as the number of active registers used) of the program being executed. An optimally programmed GPU compute device typically has many of active wavefronts.

At runtime, wavefront T0 executes until cycle 20; at this time, a stall occurs due to a memory fetch request. The scheduler then begins execution of the next wavefront, T1. Wavefront T1 executes until it stalls or completes. New wavefronts execute, and the process continues until the available number of active wavefronts is reached. The scheduler then returns to the first wavefront, T0.

If the data wavefront T0 is waiting for has returned from memory, T0 continues execution. In the example in Figure 2.6, the data is ready, so T0 continues. Since there were enough wavefronts and processing element operations to cover the long memory latencies, the compute unit does not idle. This method of memory latency hiding helps the GPU compute device achieve maximum performance.

If none of T0 – T3 are runnable, the compute unit waits (stalls) until one of T0 – T3 is ready to execute. In the example shown in Figure 2.7, T0 is the first to continue execution.

Building and Running OpenCL Programs¶

An OpenCL application consists of a host program (C/C++) and an optional kernel program (.cl). To compile an OpenCL application, the host program must be compiled; this can be done using an off-the-shelf compiler such as g++ or MSVC++. The application kernels are compiled into device-specific binaries using the OpenCL compiler.

Compiling the Host Program¶

In order to compile the host program, users must install the OpenCL Compiler and language runtime on the ROCm, On Ubuntu is rocm-opencl-dev which provides all the necessary OpenCL runtime headers and libraries required by the host compiler. If wish to support application build with the historical APPS SDK sets an environmental variable named AMDAPPSDKROOT to the path of the directory in which the ROCm OpenCL is installed. It should be /opt/rocm/opencl. The runtime headers and libraries are placed in the install directory under the “include” and “lib” sub-folders, respectively.

While building the host program, these headers and libraries must be included in the project by choosing the appropriate options for the targeted operating system, IDE, and compiler.

Compiling on Linux¶

To compile OpenCL applications on Linux, gcc or the Intel C compiler must be installed. There are two major steps: compiling and linking.

Compile all the C++ files (Template.cpp), and get the object files.

64-bit object files on 64-bit system:

g++ -o Template.o -c Template.cpp -I$ROCMOPENCL/include

Link all the object files generated in the previous step to the OpenCL library and create an executable.

For linking to a 64-bit library:

g++ -o Template Template.o -lOpenCL -L$ROCMOPENCL/lib/x86_64

Compiling the device programs¶

OpenCL device programs that will be executed in parallel by each work-item are expressed in terms of kernel functions. The device programs may also include other helper functions (which cannot be invoked by the host) in addition to the kernels.

The device programs are written in the OpenCL C language. The device programs must be built for each target device before they can be executed on the OpenCL device. As a result, the same source program may have multiple device-specific binaries. To manage this conveniently, the OpenCL runtime provides a container-like object, called a program object, that contains the source code as well as the device-specific binaries of all the kernels and helper functions that are defined in a program scope. Compiling the application kernels requires first creating program objects.

Creating OpenCL program objects¶

In general, OpenCL program objects are created in two ways:

From the OpenCL C source

From a pre-built binary (either device-specific or device-agnostic)

Creating program objects from the OpenCL C source¶

In this method, the OpenCL C source is passed to the clCreateProgramWithSource runtime API (for more details, see the OpenCL

specification) as a text buffer to create the program object. If the source code is in an external file, then it must be read and placed in a text buffer before passing the buffer to the API.

Note: Most of the examples in this chapter are shown using runtime C APIs. In order to use the C++ wrapper APIs, one must map (a trivial step) the C APIs to corresponding C++ wrapper APIs. For cleanness, error checking is not shown.

Example creation of program objects from an inline text string :

const char *source =

" kernel void myKernel( global uint *src, global uint *dst)\n"

"{ \n"

" uint gid = get_global_id(0); \n"

" dst[gid] = src[gid] * 10; \n"

"} \n";

cl_program program = clCreateProgramWithSource( context, 1,

&source, NULL, NULL );

Example creation of program objects from an external file :

std::ifstream f("my_kernel.cl");

std::stringstream st;

st << f.rdbuf();

std::string ss = st.str();

const char* source = ss.c_str();

const size_t length = ss.length();

cl_program program = clCreateProgramWithSource(context, 1, &source,

&length, NULL)

Creating program objects from a pre-built binary¶

OpenCL allows the creation of program object from binaries previously built for one or more specific device(s) or from intermediate device-agnostic binaries (using, for example, the Standard Portable Intermediate Representation (SPIR) format). Such binaries serve two useful purposes:

Software vendors can protect their IP by supplying the OpenCL library as a collection of pre-built binary programs instead of as raw source code.

The consumer of the OpenCL library can create new program objects using those binaries for use with their own applications.

In this method, the OpenCL binary is passed to the binaries argument of the clCreateProgramWithBinary runtime API (for more details, see the OpenCL specification). If the binary program code is in a file, the binary must be loaded from the file, the content of the file must be placed in a character buffer, and the resulting buffer must be passed to the clCreateProgramWithBinary API.

Building the program executable from the program objects¶

After the program object is created (from either sources or binaries), the program must be built for the targeted devices and the device executables must be generated. The executables are generated mainly in two ways:

Building (compile and link) the program in a single step (using clBuildProgram)

Compiling and linking the program separately (using clCompileProgram and clLinkProgram)

Building the program in a single step¶

The most common way of building program objects, this method uses a single API, clBuildProgram, for both compiling and linking the program. For additional details about this API, see the OpenCL specification.

Example(s):

- Suppose a program object has been created as follows:

- cl_program program = clCreateProgramWithSource(context, 1, &source,&length, NULL);

Next, the program object can be built for all the devices in the context or for a list of selected devices.

To build the program for all the devices, “NULL” must be passed against the target device list argument, as shown below:

clBuildProgram(program, 0, NULL, NULL, NULL, NULL);

To build for any particular GPU device or a list of devices :

int nDevices = 0;

clGetDeviceIDs(platform, CL_DEVICE_TYPE_GPU, 0, NULL, &nDevices);

cl_device_id * devices = malloc(nDevices * sizeof(cl_device_id));

clGetDeviceIDs(platform, CL_DEVICE_TYPE_GPU, nDevices * sizeof(cl_device_id), devices, NULL);

To build for the nth GPU device in a list of devices:

clBuildProgram(program, 1, &devices[n], NULL, NULL, NULL);

To build for the first n number of GPU devices

- ::

clBuildProgram(program, n, devices, NULL, NULL, NULL);

Build Options:

A list of options can be passed during program build to control each stage of the building process. The full list includes various categories of options, such as preprocessor, compiler, optimization, linker, and debugger. Some of them are standard (specified by Khronos); others are vendor-specific. For details about the standard options, see the clBuildProgram API’s description in the OpenCL specification.

For information about the frequently used standard build options, see “Supported Standard OpenCL Compiler Options”.

For information about AMD-developed supplemental options and environment variables, see “AMD-Developed Supplemental Compiler Options”.

Special note for building OpenCL 2.0 programs:

In order to build the program with OpenCL 2.0 support, the -cl-std=CL2.0 option must be specified; otherwise, the highest OpenCL C 1.x language version supported by each device is used when compiling the program for each device.

OpenCL 2.0 is backwards-compatible with OpenCL 1.X. Applications written on OpenCL 1.x should run on OpenCL 2.0 without requiring any changes to the application.

Special note for debugging:

OpenCL provides a way to check and query the compilation/linking errors that occur during program build. Various build parameters for each device in the program object can be queried by using the clGetProgramBuildInfo API. Retrieving the build, compile or link log by using the CL_PROGRAM_BUILD_LOG input parameter is a useful and frequently-used technique. For details, see the OpenCL specification.

Example:

cl_int err = clBuildProgram(program, 1, &device, NULL, NULL, NULL);

if (err != CL_SUCCESS)

{

printf("clBuildProgram failed: %d\n", err);

char log[0x10000];

clGetProgramBuildInfo( program, device, CL_PROGRAM_BUILD_LOG, 0x10000, log, NULL);

printf("\n%s\n", log);

return -1;

}

Compiling and linking the program separately¶

In this method, two separate steps are performed to generate the device executable. First, program objects are compiled by using the clCompileProgram API (for details, see the OpenCL specification); then the compiled programs are linked together to generate the final executable by using the clLinkProgram API (for details, see the OpenCL specification). This method is particularly useful– and is the only way–to link a previously-compiled program. By using this method, users can link their program objects with external program objects to build the final program object.

Both the APIs support similar options (depends on whether one is compiling or linking) as the options in clBuildProgram, to control the compiler and linker. For details about the options supported by each API, see the respective API description section in the OpenCL specification.

Compiling the program

The user must compile each program object separately. This step may be a little tedious if a source program depends on other header files. In that case, separate program objects corresponding each header file must be created first. Then, during compilation, those header programs must be passed as embedded headers along with the intended program object.

Example (derived from the OpenCL specification):

Consider the following program source:

#include <foo.h>

#include <mydir/myinc.h>

__kernel void image_filter (int n, int m, constant float *filter_weights,

read_only image2d_t src_image, write_only image2d_t dst_image)

{

...

}

This kernel includes two headers, foo.h and mydir/myinc.h. So first create the program objects corresponding to each header as follows:

cl_program foo_pg = clCreateProgramWithSource(context, 1, &foo_header_src, NULL, &err);

cl_program myinc_pg = clCreateProgramWithSource(context, 1, &myinc_header_src, NULL, &err);

Suppose the program source described above is given by program_A and is loaded via clCreateProgramWithSource.

Now, these headers can be passed as embedded headers along with the program object

cl_program input_headers[2] = { foo_pg, myinc_pg };

char * input_header_names[2] = { “foo.h”, “mydir/myinc.h” };

clCompileProgram(program_A, 0, NULL, // num_devices & device_list

NULL, // compile_options

2, // num_input_headers

input_headers,

input_header_names,

NULL, NULL); // pfn_notify & user_data

Linking the program

In this phase, multiple pre-compiled program objects are linked together to create a new program object that contains the final executable. The executable binary can be queried by using clGetProgramInfo and can be specified to clCreateProgramWithBinary, as shown earlier.

Example :

Assume there are two pre-compiled program objects, program_A and program_B. These two can be linked together as follows:

cl_program program_list[] = { program_A, program_B};

cl_program program_final = clLinkProgram(context,

0, NULL, // num_devices & device_list

NULL, // compile_options

2, // num_input_programs,

program_list, // const cl_program

*input_programs,

user_data

NULL, NULL, // pfn_notify &

NULL); // errcode_ret

Supported Standard OpenCL Compiler Options¶

The frequently-used build options are:

-I dir — Add the directory dir to the list of directories to be searched for header files. When parsing #include directives, the OpenCL compiler resolves relative paths using the current working directory of the application.

-D name — Predefine name as a macro, with definition = 1. For -D name=definition, the contents of definition are tokenized and processed as if they appeared during the translation phase three in a #define directive. In particular, the definition is truncated by embedded newline characters. -D options are processed in the order they are given in the options argument to

clBuildProgram.

For additional build options, see the :ref:OpenCL specification.

AMD-Developed Supplemental Compiler Options¶

The following supported options are not part of the OpenCL specification:

-g — This is an experimental feature that lets you use the GNU project debugger, GDB, to debug kernels on x86 CPUs running Linux or cygwin/minGW under Windows. For more details, see Chapter 4, “Debugging and Profiling OpenCL.” This option does not affect the default optimization of the OpenCL code.

-O0 — Specifies to the compiler not to optimize. This is equivalent to the OpenCL standard option -cl-opt-disable.

-f[no-]bin-source — Does [not] generate OpenCL source in the .source section. For more information, see Appendix C, “OpenCL BinaryImage Format (BIF) v2.0.” by default, this option does NOT generate the source.

-f[no-]bin-llvmir — Does [not] generate LLVM IR in the .llvmir section. For more information, see Appendix C, “OpenCL Binary Image Format (BIF) v2.0.” By default, this option GENERATES the LLVM IR.

-f[no-]bin-amdil — Does [not] generate AMD IL in the .amdil section. For more information, see Appendix C, “OpenCL Binary Image Format (BIF) v2.0.” By default, this option does NOT generate the AMD IL.

-f[no-]bin-exe — Does [not] generate the executable (ISA) in the .text section. For more information, see Appendix C, “OpenCL Binary Image Format (BIF) v2.0.” By default, this option GENERATES the ISA.

-f[no-]bin-hsail — Does [not] generate HSAIL/BRIG in the binary. By default, this option does NOT generate HSA IL/BRIG in the binary.

-save-temps[=<prefix>] — This option dumps intermediate temporary files, such as IL and ISA code, for each OpenCL kernel. If <prefix> is not given, temporary files are saved in the default temporary directory (the current directory for Linux, C:Users <user>AppDataLocal for Windows). If <prefix> is given, those temporary files are saved with the given <prefix>. If <prefix> is an absolute path prefix, such as C:yourworkdirmydumpprefix, those temporaries are saved under C:yourworkdir, with mydumpprefix as prefix to all temporary names. For example,

-save-tempsunder the default directory_temp_nn_xxx_yyy.il, _temp_nn_xxx_yyy.isa-save-temps=aaaunder the default directoryaaa_nn_xxx_yyy.il, aaa_nn_xxx_yyy.isa-save-temps=C:youdirbbbunder C:youdirbbb_nn_xxx_yyy.il, bbb_nn_xxx_yyy.isa

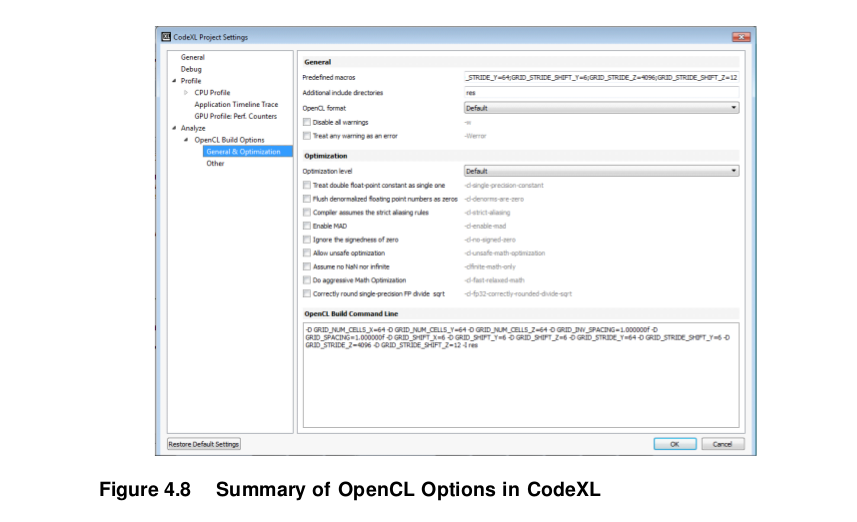

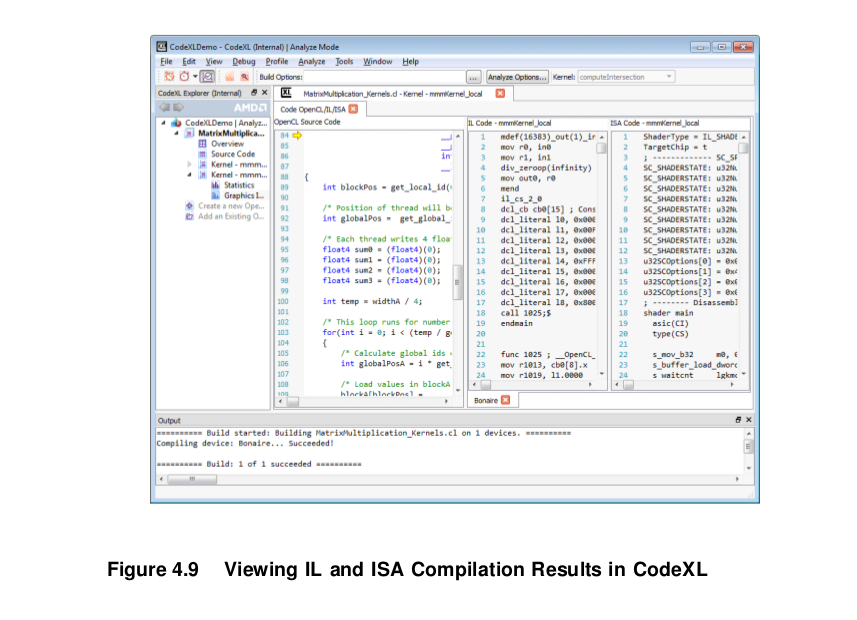

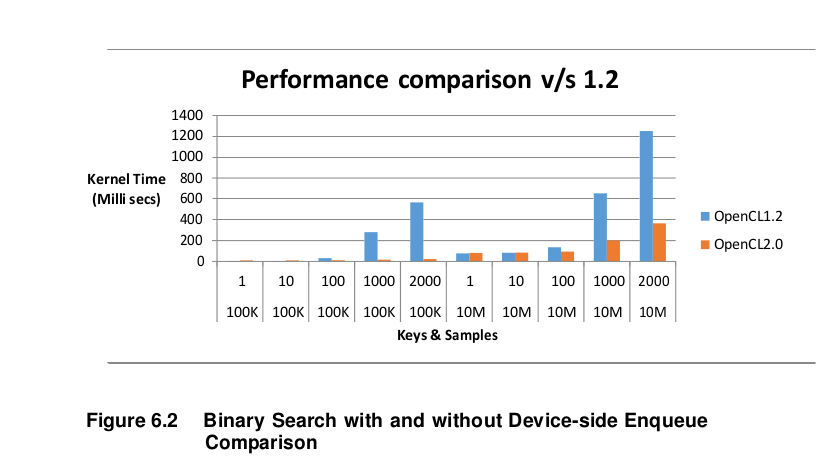

where xxx and yyy are the device name and kernel name for this build, respectively, and nn is an internal number to identify a build to avoid overriding temporary files. Note that this naming convention is subject to change.